Park fall

While over-paying to upgrade downtown, Lex leaders under-funded 414 parks across city

Late last month, a group called Parks Sustainable Funding debuted a glitzy website that advocates for a November tax ballot referendum to let citizens vote on whether to create a new Lexington tax stream to fund city park projects.

If approved, the referendum will generate $8 million annually into a Parks Fund by imposing a tax of 2.25 cents per one hundred dollars ($100.00) on all real property. The projected cost to “the average Lexington home owner,” Parks Sustainable Funding claims, will be around $55 per year. You can read more about the specifics of the referendum in this write-up by Paul Oliva.

Like most people here, I love my parks and make use of them often. You can see this in a lot of my work. I made an early writing decision to cover local sports like Bike Polo and Disc Golf and Bocce Ball, which often sent me and other volunteer writers who I edited into city and regional parks like Coolavin, Veterans, Shilito, the Rhiney B and Courthouse Square.

Local parks and other public places also crop up in my satire, fiction, civic proposals, city travel documentaries, mayoral campaigns, and other creative writing outlets. As my daughter has aged, her own developing interests and friend networks have sent me into a wholly different set of community parks, all of which I find wondrous, for all of the good reasons cited by the folks at Parks Sustainable Funding.

This post will look at the research used by Parks Sustainable Funding to arrive at its tax referendum’s .0225 levy rate. The group’s main source is a 2018 Parks Master Plan document that “found $100 million dollars in capital needs” at parks located throughout Lexington. (As the referendum has sped through LFUC Council subcommittees, the backlog amount appears to have risen to $120 million dollars, or 15 years of $8 million “catch-up” transfers from the proposed Parks Fund levy.)

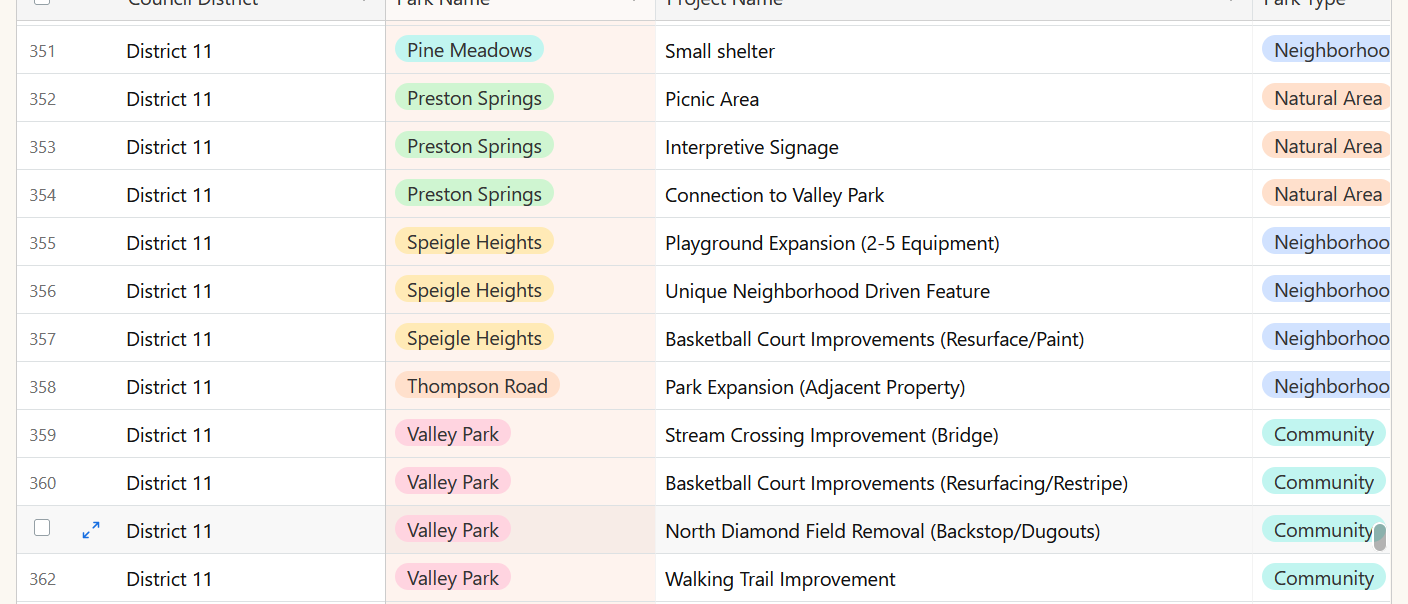

The large backlog of park projects is a pretty damning snapshot of the previous 15 years of city development. In total, our leaders of yesteryear left city residents with 414 unfinished projects spread across 95 different parks located in all 12 LFUC Districts.

Helpfully, the Parks Sustainable Funding folks include the backlog list in table format on their webpage, so you can check things out for yourself.

Parks Sustainable Funding does not say how things got this bad, nor does any other reporting outlet. But I’m here to tell you, the disinvestment was by design, not drift.

The previous 15 years of Lexington development are notable for the widespread use of public-private partnerships to develop and leverage the Lexington Brand, imagined as a quaint but progressive downtown set amidst bluegrass horse country. Leaders of the Make Lexington Great Again (MaLGA) movement have long argued that big ticket, complex, subsidized investments to globalize the Lexington Brand are harmlessly revenue-neutral and actively beneficial to the greater public.

The sheer scale of capital backlogs for city parks, however, suggest otherwise. Recent city growth was neither revenue neutral nor for the greater Lexington good.

My recent reporting on the 30-year CentrePointe TIF, an early MaLGA project, suggest one likely contributing factor to the current scale of under-capitalized park projects: a starve-the-beast tax policy. In 2022 alone, over $900,000 in local taxes generated within a designated three acre urban TIF zone were diverted to CentrePointe Parking Services, LLC. The tax diversions were made as payment for construction of a 700 car underground parking garage to service customers of the above-ground CentrePointe development.

Collectively, these and other similar public-private contracts choke General Fund tax growth. The accumulating chokepoints stress long-standing budget commitments for everyday city services. Policing, pot-hole fixing and, yes, parks maintenance.

But Lexington leaders erred a second way. They over-valued the importance of downtown and horse country to the well-being of its own residents. The MaLGA idea to commit over a billion dollars into a very small downtown geographic area—4 TIFs, a convo center, 2 bike trails, Community Development Block Grants, boutique hotels; etc. etc.— required Lexington leadership to intentionally siphon community assets from elsewhere in the county.

This failure wasn’t simply Shrink the budget! conservatism. It was Send all budget resources here! here! and here! cosmopolitanism.

Take for example the $300-400 million Rupp Arena renovation. Over the past decade, the city gave over $10 million in General Fund money to seed the Rupp project, then pooled federal transportation (TIGER) grants to complete a $45 million greenway to it, then enacted a 2.5% increased hotel tax across the county to continue paying for it, and then sucked up philanthropic park donations by stumping for a $35 million privately-funded park to get built behind it.

If you lived in Harrod’s Hills or Cardinal Valley or most any other city neighborood, your community was effectively put on hold for over a decade to make Rupp happen, based on the cosmopolitan argument that a “gold standard” Rupp would improve Lexington lives.

In 2011, I speculated on this progressive misallocation of city value. As it turns out, in 2011 District 9 had a parks champion, former council member Jay McChord, who had scraped together $2.5 million in park projects for his district across four years in office.

Here is my 2011 accounting of his investment:

McChord’s $2.5 million investment has resulted in over 100 acres of new park land opening up across the district. At Shilito Park where much of the money was directed, funding produced a 2.25 mile healthway trail, improvements to a number of baseball fields, a resurfaced tennis complex, space for soccer and lacrosse, and expansion of a disc golf course. In addition, the $2.5 million investment netted other area parks playground equipment, four more healthway trails, a dog park, rain gardens, native plantings and a “sensory garden.”

My argument for the value of District 9 park investments mirrored those made 13 years later by Parks Sustainable Funding leaders.

In the Ninth District, the $2.5 million in public/private funds built community value by creating publicly accessible spaces of healthy activity, leisure and transportation. Park upgrades also built property value and connected geographically disperse suburban neighborhoods and people, from mall rats on Nicholasville Road beyond New Circle to Unitarians attending church on Clay’s Mill nearby Man O’War.

But in 2011, I also made clear value judgements between different city-leveraged projects. (We used to call this leadership.)

Meanwhile, city business leaders have called for an initial $300 million investment to be poured into Rupp’s 50 downtown acres. In terms of value for city residents, that should work out to a project with 120 times the value as McChord’s Ninth District funding for parks. Rupp won’t even come close.

More than a decade after writing that, an updated comparison is revealing.

Lexington does indeed now have a truly gold standard Rupp renovation, an enlarged convention center, an award-winning urban greenway, and a nearly complete urban park. Lexington is great again!

We also, according to the Parks Master Plan, now hold a 32 project backlog at 6 different Lexington parks located in McChord’s District 9.