A reminder: Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Speech

Third Parties emerge during moments of great national distress to push entrenched powers to change their views. That’s a great thing.

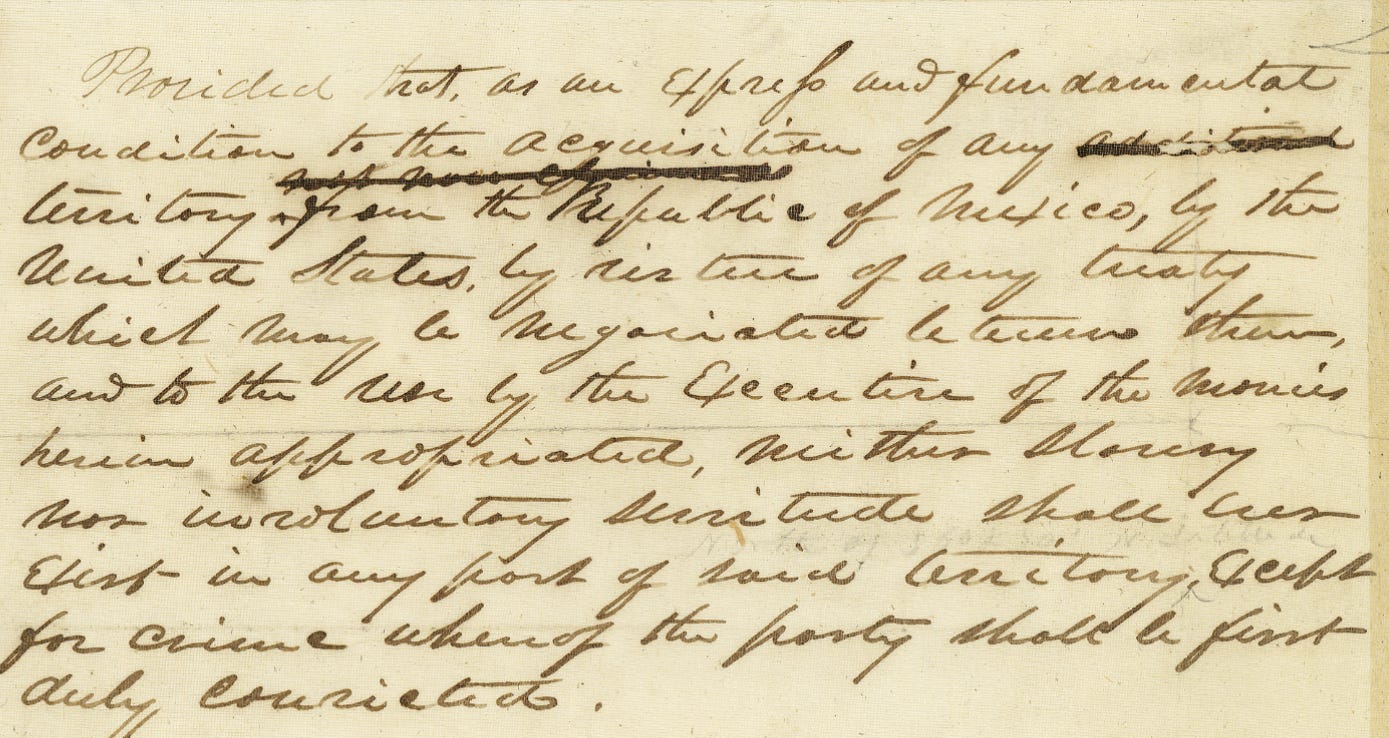

In 1846, a Pennsylvania Congressman, David Wilmot, attached a 71-word Congressional amendment to the treaty to end the U.S. war with Mexico.

Under conditions of the 1846 treaty, the U.S. government promised payment to Mexico of $2 million ($82 million in 2024 dollars) in exchange for American ownership of all of present day California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico; most of Arizona and Colorado; and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas and Wyoming.

Wilmot’s proviso to the treaty made any federal payment to Mexico conditional upon the prohibition of slavery in all newly ceded western territory. It passed the House but was defeated in the Senate and ultimately not included in the final treaty with Mexico.

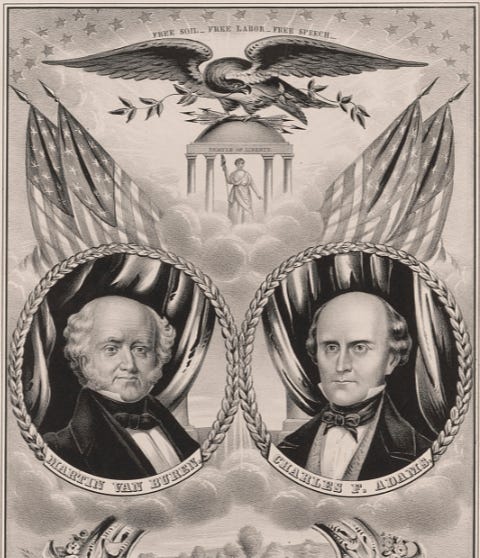

The Wilmot Proviso may have been a footnote in history, but two years later, it would birth a political party of misfits, The Free Soil Party. A loose coalition of aging loco focos, youthfull barn burners, conscience Whigs, Bay State Whiggers, members of the Liberty Party and of the Cincinnatti Clique, Wentworth Men and Hale Men, Ohio Hards, abolitionists, Wooly Heads and a whole bunch more, Free Soilers embraced what was essentially a one-trick pony platform: the hard-headed, line-in-the-sand, weirdo, unconditional, damn the torpedoes we’re going straight on until sunset support for Wilmot’s idea. No slavery in the new territories.

The party motto went, Free Soil. Free Labor. Free Speech. Free Men.

I am thankful for these American nutso’s, who I sort of envision as an antebellum version of the muppets on a cross-country ramble. Their 1848 Free Soil Party campaign for the U.S. Presidency won no votes in the electoral college, yet it had some pretty world-altering effects. It smashed open a stagnant two-party political system that had attempted to ignore the issue of slavery, fatally fractured Henry Clay’s wishy-washy Whig party, and cleared the field for what emerged from the ashes as the anti-slavery Republican Party, the party of Lincoln.

Here is how the Free Soilers did it.

I. Deplorable leadership

David Wilmot, author of the proviso that begat the Free Soilers, was a Democrat congressman from Butler County, Pennsylvania. Incidentally, this is the county where, 178 years later, the first assassination was made on Donald Trump. It is Deplorables country.

Deplorable is probably how we would view Wilmot today. The antebellum Congressman was against the extension of slavery into the western territories because it devalued white artisan and other labor. Of his Proviso, which he referred to as the “White Man’s Proviso,” Wilmot said,

I have no squeamish sensitiveness upon the subject of slavery, nor morbid sympathy for the slave. I plead the cause of the rights of white freemen. I would preserve for free white labor a fair country, a rich inheritance, where the sons of toil, of my own race and own color, can live without the disgrace which association with negro slavery brings upon free labor. […]Where the negro slave labors, the free white man cannot labor by his side without sharing in his degradation and disgrace.

In this belief, Wilmot was like nearly all Free Soiler factions save the factions of abolitionists from the Liberty and Whig parties. Led by the Barnburners, rural Democrats from upstate New York who, the historian Eric Foner writes, “came from a political tradition hostile to Negro rights and accustomed to the use of race prejudice as a political weapon,” the Free Soil position against slavery hinged upon white class interests.

This class criticism of slavery had gained credence throughout the 1840s. Slavery, the free soil argument went, suppresses local wages and inhibits the development of “free” white labor and industry. None other than Walt Whitman, writing as city reporter in the Brooklyn Eagle, would voice free soil ideals when counterposing

the grand body of white workingmen, the millions of mechanics, farmers and operatives of our country, with their interests on one side—and the interests of the few thousand rich and aristocratic owners of slaves at the South, on the other.

For the Conscience Whigs and former Liberty Party members who believed generally in the full equality of slaves, their support meant subordination of their own personal beliefs on abolition to what they viewed as a more crude free soil economic argument for banning slavery in all the new territories.

II. Renegade Acts & Trusting the Other

While the Wilmot Proviso provided the organizing force, the Free Soil party came into existence through a series of renegade political acts across the non-slave states that defied both Democrat and Whig leadership.

Both parties had to appeal to their different northern and southern bases, and both had desires to grow their base into the western territories. In southern states like Kentucky, both Whigs and Democrats were pro-slavery, which made both southern party coalitions uniformly opposed to its abolition.

For national reasons, southern Whigs like Henry Clay were required to make general appeals to the disagreeableness of slavery and the far-off possibility of a nation without the institution. But at the end of the day, southern Clay Whigs were, like Henry himself, mostly themselves slave owners. The soft pro-slavery position of Clay Whigs in turn allowed southern Jacksonian Democrats to vocalize an unapologetic support for the institution.

In northern states, however, both Democrats and Whigs contained factions increasingly critical of slavery. The northern Whig party was dominated by Cotton Whigs, northern mercantilists who profited from the industrialization of the southern plantation economy. They were opposed by Conscience Whigs, who comprised what we might now call the professional-managerial-academic classes that sought to abolish slavery on religious and ethical grounds.

Northern Democrats, meanwhile, contained two factions, (1) small-scale white rural farmers and (2) recent urban immigrants, who had been long-standing beneficiaries of the development of the western frontier.

As the 1848 Presidential election heated up, neither major party appeared capable of addressing head-on the pressing issue of slavery in the newly acquired western territories. The competing political interests and affections had produced a strategy for both parties described by historian Joseph Rayback as one of “compromise and evasion.”

This inert status quo may have remained but for the actions of renegade factions within both the Whig and Democrat parties. First to push was a faction of nutso rural New York Democrats who threatened to leave the Democrat party in 1847 over the party’s refusal to endorse a free soil position. Derisively named for their supposed desire to burn down the foundations of government to achieve their anti-corporate (and now anti-slavery) views, the Barnburners withdrew from the May 1848 National Democratic Convention held in Baltimore when the party would not endorse a free soil position.

In leaving the Democrat’s Convention, the Barnburners had broken through the “our democracy” guardrails of their day. They issued a call for a June 21 convention in Utica to nominate their own Presidential candidate. News traveled far and wide.

Whig defections, meanwhile, occurred soon after its own national nominating convention, also held in May, in the city of Philadelphia. In Ohio and Illinois and all along the Eastern seaboard, Whig papers declared that they would not support the 300 slave-owning Whig nominee for President, Zachary Taylor of Loserville.

In Ohio, the historian Raybeck writes, “nearly a thousand Ohioans of all parties [Whig, Democrat, Liberty] gathered at the state capital.” At the meeting, which took place a day before the Barnburners’ Utica convention, the group declared themselves “Friends of Freedom, Free Territory and Free Labor, willing and desirous to cooperate with any party thoroughly resolved and inflexibly determined to permit no further extension of slavery.” The Columbus meeting ended with a national call to meet in Buffalo, New York, on August 9 to nominate a Presidential candidate.

A week later in Worcester, Massachusetts, a crazy gaggle of Conscience Whiggers held a large rally in support of their free soil inflexibility. Their meeting also ended with a call to re-convene in Buffalo. From here, Whig and Democrat defections intensified. Raybeck writes,

In Indiana, hitherto relatively untouched by third-party appeals, and in Michigan…statewide conventions and scores of local meetings named Buffalo delegations resolved ‘to bury all political animosities and strike hands for the one great cause of Free Soil and Free Labor.’ Northern Illinois and southeastern Wisconsin witnessed scenes of similar activity. In Chicago vast throngs of Whigs and Democrats marched the streets chanting the name of the Utica nominee. Every county of the region saw members of the major parties uniting in the movement to ‘bar slavery’ forever from the western plains. Signs of anti-slavery attitudes also began to appear in Iowa.

In August, as delegates arrived to Albany from across the free states for the Free Soil convention, nobody knew what exactly to expect. For twenty years, Whigs and Democrats had increasingly come together to form a consensus on the issues–tariffs, banking, internal improvements– that had originally differentiated them. As their views merged, however, the two parties increasingly engaged each other as mortal enemies, with much of the ire focused on Andrew Jackson, the Democrat from Tennessee who was twice elected President—the Donald Trump of his era.

In Albany, these former partisan warriors eyed each other warily. Barnburners feared a platform too morally aligned with the Conscience Whigs and Liberty Party members. Whigs, for their part, had to swallow supporting the former Democrat President—Jackson’s handpicked successor!—Martin Van Buren for the presidential candidate.

But they did it, and in breaking the rules of their Old Parties, those renegades created the pathway leading to a Free Soil nation, one purged of legal slavery.

III. Moving right along

Like nearly all political movements from our past, Free Soil’s constituent groups were not uniformly right (from our present perspective) in how or for what or whom they politically advocated. Nor were they immediately successful. (Nor did they expect to be.) Van Buren did not win a single state in ‘48. The party lasted less than a decade before going the way of the Whig party it helped destroy. Today it is mainly categorized as a proto-nativist party like the Know Nothings and the American Party, where southern Whigs and a few northern Democrats had moved to after the 1848 election).

Even in losing, though, Free Soil was successful. They simply did not let slavery become a quiet and compromiseable issue. In attracting a bi-partisan coalition in the north, Free Soil transformed the Democrat party into a sectional, pro-slavery party of southerners. Meanwhile, it helped take down the Whig Party, whose views on slavery had mostly mirrored the Democrats.

In the churn of these confidently renegade Free Soil factions and forces there was created a dynamic American marketplace that I can’t help but admire. Abuzz with cultural and governing ideas from all parts of the country, the emergent uncompromising vision would help spawn a Republican Party fully committed to universal abolition. Free Soil had demonstrated proof of concept: slave power could be defeated. It just took some crazy people to call nonsense on respectable Democrat and Whig leaders, and for these crazies to do the most dangerous things possible: to join with their opposition over common if not identical interests.

All this antebellum populism was surely a sign of national vigor, a barnburning testament to a shared national belief in the American political project: not only that some ones are listening, but that different groups with different or complementary ideas can leave entrenched organizations, re-gather elsewhere, and form new coalitions that attempt new solutions. From this crazy rabble we once built a bold and strong nation. Not always a correct one. Not always an empathetic one. Who or what could be that shining? But an active one, a nation of people both moving and moveable.

The fear and loathing poured upon third party formation by our modern day Democrats and Republicans who seemingly trade off Dick Cheney endorsements is surely a sign of our present intellectual and moral malaise, a psychic national fear, borne of a frumpy middle age and cornered markets, of un-endorsed thoughts and stray feelings that maybe you should consider doing something different.